12 Translanguaging in Computer Science Education

Sara Vogel; Christopher Hoadley; Lauren Vogelstein; Wendy Barrales; Sarane James; Laura Ascenzi-Moreno; Jasmine Y. Ma; Joyce Wu; Felix Wu; Jenia Marquez; Stephanie T. Jones; and Computer Science Educational Justice Collective

Chapter Overview

This chapter unpacks the term “translanguaging” and offers it as a theory to promote language justice for bi/multilingual learners in computer science education (CS Ed). It explores how translanguaging as an everyday practice is perceived in deficit ways because of power and social inequity. It also provides examples of how to interpret students’ language practices through asset-based lenses. The chapter then considers how taking up translanguaging in CS classrooms makes space for students to draw on their full language repertoires as resources for learning. It concludes by examining the three components of translanguaging pedagogy: stance, design, and shifts.

Chapter Objectives

After reading this chapter, I can:

- Define translanguaging as a theory.

- Explain how translanguaging promotes language justice for students.

- Identify stances, designs, and shifts that can be implemented to leverage translanguaging in CS pedagogy.

Key Terms:

academic language; bi/multilingual learners; critical consciousness; language repertoire; language resources; languaging; raciolinguistic ideologies; standard English; theory; translanguaging design; translanguaging pedagogy; translanguaging shifts; translanguaging stance; translanguaging theory

John’s Story

One of the first steps toward promoting language justice in CS Ed is to examine and interrogate how we as educators interpret how people, and especially our students, use language. Do we perceive students as competent communicators and meaning makers? Or do we instead focus on deficits and what students lack? While most teachers want to do the former, we may find ourselves doing the latter when students express meaning in ways that we are not accustomed to or find difficult to parse, or when we don’t have enough time to stop and think about what our students are really trying to do.

In this chapter, we revisit John, a sixth grade student in a New York City public middle school who had immigrated to New York City from Eritrea in East Africa during fifth grade. From John, we can learn how to more sensitively interpret what students say and do in ways that promote equity.

As we learned in Chapter 11, John used four languages in his daily life: Amharic, Arabic, English, and Tigrinya. Labeled as an English Language Learner (ELL) by the district when he enrolled in school, John was placed in an English as a New Language (ENL) class. His ENL teacher, Ms. Kors, worked to integrate CS into their class. She asked her students to use Scratch to tell a family story. John decided to animate an important moment in his family’s history: when he and his family walked from Eritrea to Ethiopia for three days at the beginning of their journey as refugees.

In the classroom moment below, John interacts with a Participating in Literacies and Computer Science (PiLa-CS) researcher.[1] As you read this example, we invite you to consider the perspectives you bring: How would you interpret what John is meaning here?

Interpreting Language Practices

In order to create his family history Scratch project, John had to become acquainted with many computational ideas and make choices to express his ideas in code. During this process, John wanted to program his sprites (or characters) to speak one at a time, which required him to carefully sequence “wait () secs” code blocks between the blocks for the characters’ dialogue.

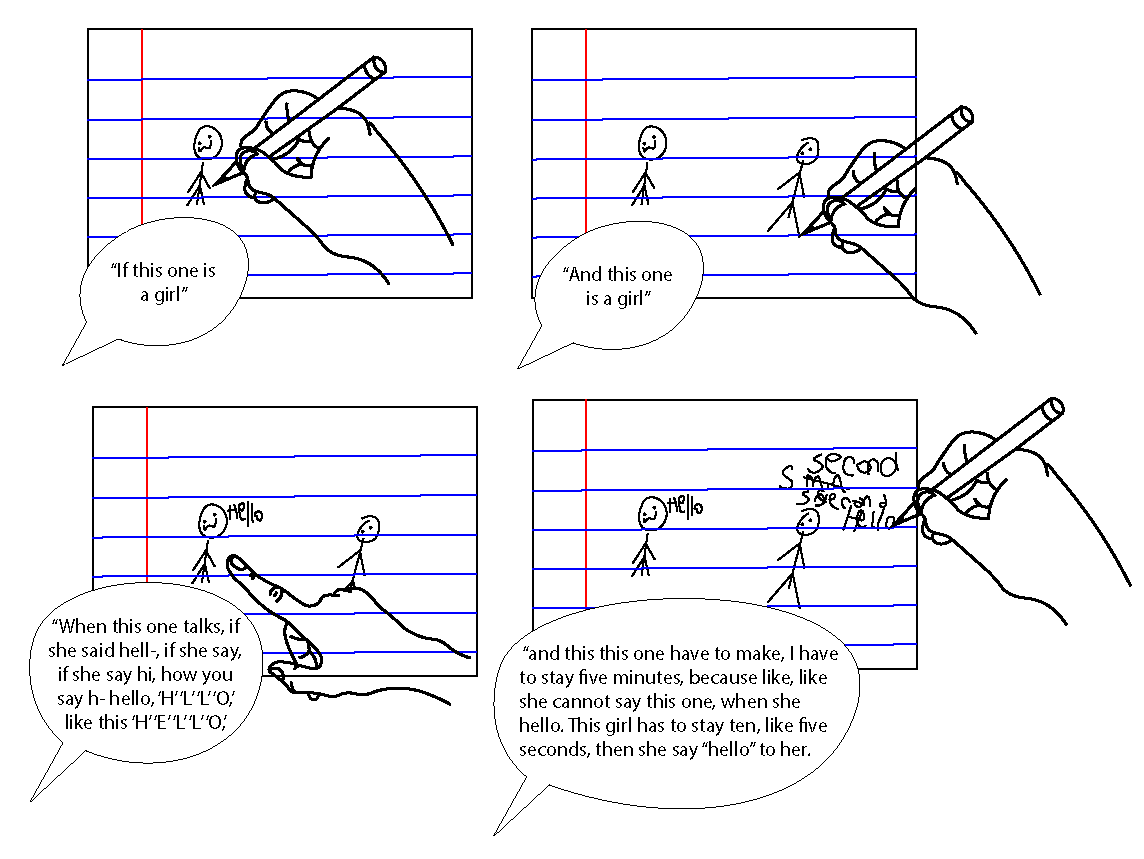

John was asked by a PiLa-CS researcher to explain how this code functioned. In his explanation, John drew two different stick figures representing Scratch sprites and then shared how he wanted them to greet each other using spoken language and gestures. The following captures part of John’s explanation:

How do you interpret what John is meaning here? (Excerpted from Vogel [2020].)

Interpreting Students’ Language Practices

There are many ways that teachers might interpret what John is doing here. When students communicate with us, we try to make sense of and interpret their communication through different theories, or sets of ideas used to explain how society works.[2] In John’s case, we draw on theories we have about how people learn language and use language to learn. Based on our theories, we make judgments about what language counts as “articulate,” “academic,” or “appropriate” in CS classrooms.

The theories that educators use to interpret language shape what they do in classrooms. For example, using a theory that connects how well a student can use “academic language” to intelligence might lead an educator to identify “problems” with how John shared his ideas. They might label what John was doing with spoken language as “stuttering,” with him “struggling” to get his words out. Using this theory, they might conclude that he didn’t understand how to code in Scratch. These kinds of deficit-based framings of students can lead educators to provide remedial education around vocabulary and conclude that some students need simplified curricula.

Other theories, however, might lead educators to interpret what John was trying to communicate in a different way. These theories help educators recognize and parse all of the resources — language and communication tools — that John orchestrated in his explanation. John coordinated his words with drawings and gestures and even went on to expand his explanation by asking the researcher to act out the conversation idea together, embodying what it meant for talk to overlap. If our theories help us attend to these many resources, we can recognize that John had an in-depth understanding of the idea that in an animated dialogue, wait time must be programmed in, even if humans take it for granted in a conversation. He also demonstrated his understanding of how code in the language of Scratch is spatially organized.

Attending to all of John’s communicative resources would help an educator develop asset-based perspectives on his learning, creating more opportunities for John and other students to fully express themselves. Below, we introduce a theory from linguistics, sociolinguistics, and bilingual education called translanguaging that can help us view students through asset-based perspectives.

What Is Translanguaging?

Translanguaging theory offers a way to center the dynamic and fluid ways that people use language. It helps educators pay attention to the full range of ways that students communicate, without evaluating them against a perceived “standard” way of speaking.

Translanguaging theory calls attention to how there are two ways of thinking about what language is. When used colloquially, “language” might be used as a noun to refer to a collection or system of sounds, syntaxes, signs, and symbols, which have been politically labeled with a name: Arabic, English, Hindi, Mandarin, Spanish, and so on. But “language” can also refer to the act of communicating itself, a verb. This definition highlights that language is a general competence. Bilingual education scholar Ofelia García uses the verb languaging to reflect that language is something people do in social contexts. Languaging and communication are universal capacities, even if using particular language systems like English, Mandarin, and Spanish are not. Translanguaging theory captures this idea.

Translanguaging Theory

Translanguaging theory posits that:

- People have only one system of language features and practices — one general language repertoire — that they draw on to make meaning, learn, and express themselves.

- These features and practices defy the named languages (English, Spanish, etc.) that society has used to categorize language (García & Wei, 2014) .

To unpack this theory, let’s start with the first part: people have one language repertoire.

Just like John, all of us have a collection of resources we use to communicate, make sense, and learn. That collection includes words, sounds, syntaxes, gestures, signs, symbols, objects (like things in our environment, clothes, media, and tools), and social knowledge about how, when, and where to use those forms in different contexts. We call that collection our communicative repertoire (Rymes, 2014) or our language repertoire. The features of that repertoire are our language resources.

Translanguaging recognizes that people have one, unified repertoire of language features and practices that they draw on when they communicate and make meaning. In recognizing this, translanguaging attempts to rectify past theories that argued that different languages (like Arabic, English, and Spanish) lived separately in the mind. According to those theories, when people communicate, they access each mental system separately, with bilinguals only being able to use one of their different systems at any time. This kind of argument led to misconceptions that there was only so much “space” in the brain for different languages. Operating with those traditional language theories, educators would probably insist John use his home languages less to reduce confusion, problematically neglecting the assets of his language repertoire, and being complicit in assimilationist forms of education.

Translanguaging theorist Dr. Ofelia García argued that these older theories didn’t capture the dynamic ways that most people, and especially bi/multilingual people, actually do language (García, 2009).[3] For example:

- In talking with bilingual friends, bilinguals often use words from different languages in the same sentence to capture concepts and ideas that don’t translate.

- A bilingual physics student from Latin America who studied abroad in the United States might be nervous about giving a research talk in what would be considered her “native” language, Spanish, because she learned concepts and ideas about physics in English.

- Many young bilinguals in the United States are encouraged to practice English and not to speak a home language at home. They may be more comfortable listening to and understanding a home language than English but more comfortable speaking and writing in English than their home language.

Traditional theories would suggest that individuals in the circumstances above were less “balanced bilinguals” or were more “dominant” in one language over another. But that idea locates deficiencies and differences in those bilingual people relative to a monolingual standard. Bilinguals are not two monolinguals in one (Grosjean, 2012). As García and others have pointed out, people don’t use or acquire languages as they appear in the dictionary. We acquire and use different language resources depending on the context around us and our purposes for communicating.

Another major limitation of traditional language theories is that they posit that named languages are a reality in our brains. But named languages (French, Hebrew, Hindi, etc.) are social and political designations (Otheguy et al., 2015). This reality is clear when we consider the experiences of someone growing up in Scotland and someone growing up in Louisiana. While they may both be recognized as speakers of “English,” they might still find communication with each other difficult. So why are both of those people recognized as speakers of English? Moreover, why are certain minority languages, such as Occitan and Patwah, referred to as “dialects” rather than languages?[4]

One answer to this question can be traced back to colonialism, imperialism, and nation-state building. Scholar Max Weinreich captured this idea during a lecture in the 1940s:

אַ שפּראַך איז אַ דיאַלעקט מיט אַן אַרמיי און פֿלאָט

a shprakh iz a dialekt mit an armey un flot

“A language is a dialect with an army and navy”

— Max Weinreich

This quote captures that traditional power dynamics dictate the ability to decide what counts as a “language,” and what is merely a “dialect.” People speak how they speak, but politics often shape, police, or value/devalue language practices based on our conceptions of named languages.[5]

This leads to the second part of translanguaging: people’s language repertoires do not conform to the named languages (like English, Spanish, etc.) that society has used to categorize language. Translanguaging’s “trans-” prefix captures this reality. When we communicate, the ideas we have and the purposes we have for expressing those ideas determine the language we use for our thinking, not the boundaries of the named language. People draw on words, sounds, syntaxes, ideas, gestures, signs, symbols, rhythms, and cadences that they pick up from all of their life experiences.

Translanguaging can help educators attend to the many ways that our students communicate meaning, rather than solely evaluating their speech.[6] Instead of assessing John’s language against an arbitrary “standard,” we might consider all of the ways that John communicated meaning as he explained his Scratch code. This way, we get a better sense of what he understood about the computational concept of “sequencing.”

Interpreting John’s Translanguaging

Even though John only spoke in words that are recognized as English, he translanguaged, drawing on multiple communicative resources to express himself:

- John drew a quick sketch of two stick figures on either side of the page to represent two sprites (programmable objects such as characters) in Scratch (symbols).

- He wrote text next to each character, carefully sequencing their dialogue in a way that matched how a programmer would code (words).

- He gestured to one sprite and then another as he wrote, indicating who was speaking at what time (gestures).

- As he wrote the response from the second sprite, he explained and wrote a time amount on top of the sprite on the left because “this girl has to stay ten, like five seconds, then she say ‘hello’ to her,” sharing his awareness of the function of Scratch’s “wait” blocks in the context of his dialogue project (words, sounds, symbols).

Looking at how John translanguaged — how he coordinated his use of words, drawings, writing, and gestures to communicate his understanding — can help us get a better sense for what he knows and has learned.[7]

Something important to note here is that John tailored his speech to his English-speaking audience, which meant he didn’t use all of his language resources including the Amharic, Arabic, and Tigrinya he knows. Can you imagine what he could have expressed about his understanding if he had been able to use his full language repertoire?

CS teachers may allow students to use their full language repertoire without recognizing it. One teacher, Jennifer, explained, “I realize I do a ton of [translanguaging] and never gave it a name.” Jennifer described how her students use “diagrams, planning, acting, facial and hand expressions, a mix of languages [and] peer translations” to communicate and convey what they understand. Using translanguaging theory to interpret students’ communication has important implications for challenging systems of power and oppression, which we unpack in the next section.

Translanguaging, Power, and Racism

As we learned above, the language practices of people are dynamic and defy the language categories that societies have constructed. Translanguaging happens all of the time. For example, think about…

- An academic whose manuscript is filled with words specific to their field, Latinisms like “in situ” or “a priori,” or equations, charts, and graphs.

- Teens who use the latest memes to share in-jokes with each other.

- A programmer who uses code and comments to ensure others can follow progress they’ve made on an open-source project.

- The last time you sent a text message to a friend that included gifs or emojis.

- Times you used context to guess words in a science textbook that you didn’t understand.

- Times you’ve used language that would have been considered “inappropriate” or “swearing” in a situation to help you make a point.

- When deaf individuals use signs from standard sign languages as well as signs specific to their communities or families in conjunction with vocalizing and text messaging to communicate (Swanwick, 2016).

- When families with young children use made up words or imitations of their child’s pronunciation to share their affection for each other.

Some of the boundary-crossing and defying nature of the language practices described above might seem mundane to you and go unremarked upon day to day. Other examples might stick out more. This is because while translanguaging describes how everyone communicates, some translanguaging practices are more socially marked than others. Some translanguaging moves might mark someone as part of a particular community or help someone identify a certain way. For instance, using techie words and l33t speak (using characters other than letters to modify the spelling of words) might mark someone as a “geek” or “techie” person.[8] But some forms of translanguaging are marked because they are associated with groups that are assigned less or more power in society because of -isms like ableism, classism, homophobia, racism, sexism, transphobia, and xenophobia. Depending on context, when people use language associated with groups racialized as Asian, Black, Indigenous, or Latine, or language associated with immigrants, working classes, LGBTQ communities, and other marginalized groups, they might be perceived as inferior, uneducated, or transgressive.[9] When people use language currently associated with power and status (including the practices of people of white, heterosexual, cis, male, middle/upper class, college-educated backgrounds), they might be perceived as intelligent, dexterous, or creative.

Elizabeth Acevedo (2015) performs her spoken-word poem, “Afro-Latina” as a compelling example of how language gets marked differently depending on the person using it.[10] In her poem, Acevedo translanguages by leveraging a host of language resources: words that would be recognized as “English,” “Spanish,” or “Spanglish;” gestures; rhythmic phrasing; singing; and a reference to “la negra tiene tumbao” (a line from a song by Afro-Latina artist Celia Cruz). She relays her pride around her identity and unique language practices. She also shares her experiences navigating a society that does not value her and her families’ ways of being and communicating. She calls out the ways that society labeled her mother’s language “broken English” and how she internalized that stigma for a time.

Acevedo’s mother’s language was deemed “broken.” But plenty of people may use language the same way as her mother and not be stigmatized for it. For example, white American tourists who try to make themselves understood through gesture or machine translation software when they have trouble communicating with spoken language abroad are not, in general, systematically stigmatized for those practices because they are afforded more political power. Similarly, language practices used by marginalized groups might be appropriated by groups who hold more social and political power and, in the process, might be perceived as “cool” without actually affording additional power to marginalized groups.

Over the years, educators have responded to the social marking of language in a variety of ways. Historically, the approach was to help students who used language outside of a dominant norm assimilate by suppressing home languages and working to diminish their accents. As the Civil Rights movement brought attention and power to language-minoritized groups, many educators took up “additive” approaches rooted in teaching kids to “code-switch,” or recognize when it would be “appropriate” to use home languages and when to use the dominant language. This code-switching approach was intended to empower students in an unjust society (for a summary of these movements, see Flores & Rosa, 2015).

But recently, some educators have critiqued that additive approach. They have called attention to the raciolinguistic ideologies present in societies, or the ways that racism shapes dominant ideas about language. Scholars Nelson Flores and Jonathan Rosa argue that institutions and individuals become “white listening subjects” when they perceive the linguistic performance of racialized people as deviant or at a deficit, no matter how technically their speech conforms to the “standard” (Flores & Rosa, 2015). There are many examples of raciolinguistic ideologies playing out in our society and schools:

- Higher ed professors and K-12 teachers often perceived grammar errors in the speech and essays of Black and Latine students, even though the speech and writing technically complied with standard grammar rules (Alim, 2007; Flores & Rosa, 2015).

- Princess Charlotte, the young daughter of British Royals, has been praised in the popular press for growing up bilingual, while mainstream press accounts of racialized immigrant young people’s budding bilingualism is often portrayed in mainstream outlets as a problem to solve (Rosa & Flores, 2017)

- In popular culture, the Spanish practices of many Latine politicians and celebrities are often judged more harshly than those of their white counterparts (Flores, 2016).

These points highlight a key tension: even if a racialized person is code-switching and using language in ways that conform to a dominant standard, it does not mean they can overcome the effects of racism. Dr. April Baker-Bell underscores this point in her book, Linguistic Justice: Black Language, Literacy, Identity, and Pedagogy (2020).

If y’all actually believe that using “standard English” will dismantle white supremacy, then you not paying attention! If we, as teachers, truly believe that code-switching will dismantle white supremacy, we have a problem. If we honestly believe that code-switching will save Black people’s lives, then we really ain’t paying attention to what’s happening in the world. Eric Garner was choked to death by a police officer while saying “I cannot breathe.” Wouldn’t you consider “I cannot breathe” “standard English” syntax? (p. 2)

Most, if not all, educators would accept that schools should not impose a language forcibly on students or demand that they “subtract” their home languages. Yet there are still many who argue for an approach that promotes teaching students how to speak “appropriately” or to code-switch in school. Emphasizing that students should speak standard English at school or in “professional” environments suppresses their identities as emergent bi/multilinguals or speakers of marginalized varieties of language. It conveys to students that their methods of communication, and even they themselves, are inferior. The language practices our students already use are powerful, valid, and as important as “standard” English. Furthermore, these practices can support them to do CS.

Why Might Educators Take Up Translanguaging?

In schools, we often restrict students from using their full language repertoires to communicate, in part because schooling expects students to learn to use standard English in “academic” ways. Translanguaging can help educators question the nature and politics of categories like “standard English” and “academic language.” For example, translanguaging theory helps us ask:

- Why do named languages exist in the first place? Who decides what the “standard” is?

- Why are certain kinds of language (e.g. words, phrases, and styles used in Black, Latine, and working-class communities) perceived as more/less “proper” or “academic”?

- Why are block-based programming languages like Scratch perceived as less “real” than text-based programming languages like Python?

- How can we elevate speakers who use language in ways that are typically devalued in schools and CS?

- How can we notice and learn more about all of the ways students communicate, from home language practices to memes, emojis, and other digital literacies students engage in?

Translanguaging refocuses our attention on the rich and dynamic language practices that students like John already leverage in a given moment (Otheguy et al., 2015). Translanguaging helps us center students’ assets. It helps us acknowledge that all people’s language repertoires, including those of our students who may be labeled as “English language learners,” are already full and always dynamic.

By advocating for teachers to take up translanguaging perspectives, we are not saying you shouldn’t teach your students the language necessary to pass a test or ace a job interview. But your students are more than a passed test or job interview. Students should feel free to use any method of communication that will help them learn and to strategically choose the method of communication that will get them the best results in any given situation. Their diverse language practices are an asset, not a hindrance.

As we strive toward equitable practices in CS Ed, especially for students who have been marginalized for the ways they or their families use or are perceived to use language, translanguaging theory can help teachers look beyond whether their students’ language practices conform to notions like “perfect English” or “perfect Spanish” and instead pay attention to and value the rich ways students and their communities already express themselves.

When we take up a translanguaging orientation as educators, we put less stock in evaluating how students communicate against a “standard” and instead commit ourselves to help learners:

- Value their identities as bi/multilinguals or users of particular varieties used in their communities.

- Engage with complex content using their full language repertoires.

- Leverage students’ existing and complex understandings of language politics.

- Extend their language repertoires to include new practices for different contexts, audiences, and purposes.

- Navigate and push back against a world where language ideologies are imposed by society.

- Build community across language difference.

It is especially important to teach with your bi/multilingual students’ translanguaging in mind because their vast language resources are repressed in classrooms more often than many other students’ resources. Even when students have the opportunity to use more of their language repertoire than they normally do in school, they often choose not to, perhaps to better connect with their classmates. For instance, although John could have used Scratch in Amharic, he felt a need to restrict his language use to English and even raised the question if using “American” or “English” is better than his translanguaging. Resisting deficit-based language ideologies in the classroom takes time and necessitates creating trusting relationships with students. CS teacher Aaron reflected on how he might use translanguaging to build classroom relationships:

I have always looked at language as one-dimensional, not paying much mind to cultural, dialectical, and regional differences within a language. … I feel like this is a great opportunity to [use] various movies and do a “make your own captions” activity. Essentially, the student hears what the actor/actress is saying in their own words, then must translate it to how the student would say the same thing, but in their own way. This practice reflects listening and absorbing language to show its connection to how we speak for ourselves.

Aaron recognized his own limited definition of language and worked to expand it by recognizing all language varieties as valuable. His activity allows students to use their language repertoires to intentionally move between the context of the movie and their own language practices. This approach would likely build community within Aaron’s classroom.

As Aaron’s example shows, translanguaging underscores that people use different language and other expressive resources to communicate with different audiences, in different contexts, for different purposes (e.g., to express, to inform, to learn, to persuade, to push back) over their life course. Teachers can help students develop those abilities to deploy their language resources strategically and to reason explicitly about their choices.

As CS teachers who care about equitable practice, we can also support students to develop critical consciousness. Language plays a key role in that process. Students might choose to push back on dominant language ideologies. For example, educator and scholar Dr. Jamila Lyiscott (2014) shares in her spoken-word essay how she uses her different language practices in different situations and for different purposes, including to critique society.[11]

We believe that using a translanguaging lens in teaching can promote equitable practices in your classroom because it starts from the assumption that learners’ full language capacities — what they are already good at — is helpful for their learning, instead of focusing on measuring students against external named languages to demonstrate deficiencies.

Leveraging Translanguaging in Your Teaching

Students already translanguage all of the time in classrooms. Your job as a teacher is to design learning experiences and supports that help students use their dynamic and rich language resources to learn. This approach is called translanguaging pedagogy.

Translanguaging pedagogy is a way of teaching that builds on students’ diverse language backgrounds. It isn’t just accepting students’ diverse language repertoires. It involves explicitly supporting students to leverage the resources in their existing repertoires and to develop new ones.

Translanguaging pedagogy includes three parts: your stance as an educator, your designs for learning, and the shifts in practice you make to respond to students in the moment.

Translanguaging Stance

When we use the word “stance” in this context, we mean it as a belief system that shapes how you approach your students. A translanguaging stance is an orientation that frames language diversity across and within individuals as a resource, not a deficit. CS educators who practice translanguaging pedagogy take up a stance that is curious and open about students’ language practices. They learn about how students express themselves and make meaning. They also learn about students’ experiences with reading, writing, and technology in and outside of school, within the United States, and for some students, abroad.

Ms. Kors’ translanguaging stance was embodied in the family history Scratch project she designed for John’s ENL class. Ms. Kors asked students to share more about themselves and their family history, inviting them to use language practices that would be authentic to their story in the final product. John took up this invitation and shared a part of his life — his experience as a refugee — with his teacher and peers. The assignment opened up opportunities for John to be acknowledged as the full, complex, and competent community member he already was.

CS teacher Nicole reflected on how understanding translanguaging allowed her to develop a stance to resist deficit perceptions of bi/multilingual learners in her context:

In my school, I have heard the terms English as a Second Language (ESL) students, English Language Learners (ELL), English Learners (EL), and multilingual learners. I am now more aware of how using deficit-based framings has made me assess students’ language in a negative way. Unfortunately, I am sure I have made assumptions about students’ abilities which affected my students in negative ways. [After learning about translanguaging], I can bring different strategies back to my classroom to change my own practices. These efforts will advance my students’ communication skills and break some forms of language oppression.

While Nicole shared some of her initial experiences learning about translanguaging, developing a translanguaging stance is an ongoing effort. Educator Tarek Elabsy described his journey:

I’ve found that the best way to understand my students’ language practices is to be truly curious about their experiences. I try to create a classroom where they feel safe to share their thoughts and feelings about language. I also make it a point to listen carefully and really try to understand what they are communicating, even if it’s not always clear at first.

One example that comes to mind is when I was teaching a unit on coding. One of my students, Maya, was struggling with some of the programming terms. She kept using a phrase that was a combination of English and Spanish, but it made sense to her. Instead of correcting her, I asked her to explain what she meant, and she did a great job of describing the code in her own words. That moment showed me how important it is to allow students to express their understanding in ways that are authentic to them.

Tarek described how he worked to create a space that resisted assumptions about language and fostered “curiosity” and feelings of safety rather than expectations about one “right” way to use language. He also started from a belief that students were communicating in ways that made sense, even if he didn’t understand them initially. As his example with Maya shows, Tarek encouraged his students to communicate using their full language repertoires to show their understanding of concepts beyond the use of specific terminology.

Teachers who take up a translanguaging stance don’t try to police students’ language. Instead, they work to support students in making decisions about when, how, and why to use particular kinds of language for specific purposes and interactions. They teach with the awareness that language categories (like “standard” and “academic” English) are social constructs that can have real consequences in our students’ lives but that we and our students can also be empowered to resist and change (Otheguy et al., 2015).

Translanguaging Design

Armed with knowledge about their students, educators who practice translanguaging pedagogy design learning experiences that specifically support students to translanguage. The next chapters will provide approaches for designing with students’ language practices and community literacies in mind, but there are many ways to incorporate translanguaging into classroom activities.

Teachers can design lessons that encourage students to use multilingual resources. Many helpful tools are digital and exist online. For example, teachers might model how and when to use machine translation software and programming tutorials in multiple languages. CS teacher Dawn shared how she had one of her students write an essay for a local computing and social justice competition in her student’s home language and use Google Translate to generate an English version. While her student won the competition, Dawn reflected how “next time, I would encourage my students to do translanguaging throughout the essay,” drawing on all of their linguistic resources to produce their essays.

Of course, not everything is available in languages that reflect how your students communicate, so you might supplement online resources with translanguaging activities like strategically pairing students depending on the activity. Educators might pair students with similar language repertoires for activities that center fluid sense-making or group students with complementary language repertoires to encourage students to learn new language practices in English and in each other’s home languages. Other strategies could include posting multilingual word walls, having students make personal bilingual picture dictionaries, and supporting students to consider which language practices they will use to show and tell what they know. Making decisions about how and when to pair students or when to encourage certain language practices will depend on your knowledge of your students and your awareness of power dynamics related to language. The goal in implementing these strategies, however, is to give permission for students to use all of their language in the CS classroom.

Educators can also validate students’ language practices during whole class discussions and share-outs. If specialized CS vocabulary or other English learning goals are part of your lessons, you can encourage kids to use all of their language abilities to get there. Or try using activities and language that make sense to students to describe and define such terms. Let students use terms for code and programming they make up or that they use with their families and friends if these help them learn. Ask students to describe, draw, or use their bodies to express their ideas about code and computing. Looking back at how John explained the concept of sequencing, we recognize how he leveraged his multimodal language resources in his understanding and communication. Designing for opportunities like this is key for engaging in translanguaging pedagogy.[12]

Nicole, a CS teacher from New York City, shared how translanguaging designs in her after-school CS space let her multilingual learners shine. Nicole organized a 3D printing after-school program for students from all backgrounds. The students had different abilities, spoke different languages, and participated in different school tracks (e.g., gifted programs, general education, special education). Two students were often the first to finish creating using the software and the first to print. Nicole shared that they then helped “other students as they were learning the software. These two students were my multilingual learners. They were able to show students what to do. … They used [the language] they knew to express themselves and [other] students accepted their help to complete the projects. This was an amazing sight to see. … It gave my room a sense of community, computing, and different disciplines at the same time.”

Translanguaging Shifts

The design strategies we mentioned above might come in handy in the moment, as things that students say or do prompt you to make changes to your plan. Being flexible and ready to make shifts is the third part of translanguaging pedagogy.

For example, John’s teacher Ms. Kors initially wanted to have her students create Scratch projects about Greek mythology to closely align the activity with the sixth grade curriculum. However, she ultimately chose to have her students tell family stories because she wanted to get to know her students better, given that most of them were newcomers to the United States and her school. What she didn’t expect was how students themselves wanted to know more about each other’s language and cultural backgrounds. In response to these curiosities, she did things like pull up Google maps to geographically locate students’ international immigration journeys and created informal opportunities for students to ask each other questions about their language use.

Nicole shared similar small shifts she has used in her classroom to support her students to translanguage:

Using pictures or gestures definitely helps advance some forms of communication with my students. I also use Google translate and websites that change to different languages. Even changing the language … on an iPad has changed the game for me. Using the camera icon on Google translate can help when translating a kid’s writing and when I want to write for my students to understand. Using picture cards of vocabulary and having different signs with multiple languages to explain certain things have helped me to assist my students’ understanding and communication.

Supporting multilingual learners in your CS teaching doesn’t have to mean radically changing your classroom. It means adopting the three parts of translanguaging pedagogy: having a stance of curiosity and acceptance about your students’ language use and backgrounds, designing your lessons so that students can leverage all language resources, and adapting or shifting in the moment to build on the language abilities students bring to class. These techniques can also help students with Individualized Education Programs who may use language differently or help monolingual standard English speakers consider deficit language ideologies or biases embedded in their school environments.

Revisiting John’s Story

John has a rich set of resources that he used to help him complete his family story activity in Ms. Kors’ CS class. Drawing on different languages, gestures, drawing, code, and more, John was able to communicate to create and share his story. Ms. Kors’ willingness to recognize John’s different language resources as assets for learning is at the core of her translanguaging approach. Designing CS learning activities with students’ language practices at the center also requires educators to think critically about what they are asking students to learn, and why. In Chapter 13, we examine how considering computing through the lens of language can help us frame CS in more inclusive ways. In Chapter 14, we support teachers to expand learning goals beyond those covered by state standards, considering how students might blend literacies from their own communities, from computing, and from other school disciplines in generative ways.

Reflection Questions:

- How does translanguaging theory fit with or differ from how you think or have thought about language? What can you do to work toward developing a translanguaging stance as an educator?

- How have you noticed your students use their full language repertoires in different ways to make and express meaning?

- How do language policies in your settings allow people to or constrain people from using their full language repertoires?

Takeaways for Practice:

- Find a language policy relevant to your setting. Analyze it for ways that you notice how raciolinguistic ideologies or other inequities are shaping that policy.

- Analyze an existing CS lesson or activity for how well it allows students to use their full language repertoires. Revise it using translanguaging design.

Glossary

References

Acevedo, E. (2015). Afro-Latina. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tPx8cSGW4k8

Alim, S. H. (2007). Critical hip-hop language pedagogies: Combat, consciousness, and the cultural politics of communication. Journal of Language, Identity, and Education, 6(2), 161-176. https://doi.org/10.1080/15348450701341378

Baker-Bell, A. (2020). Linguistic justice: Black language, literacy, identity, and pedagogy. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315147383

Chang-Bacon, C. K. (2020). Monolingual language ideologies and the idealized speaker: The “new bilingualism” meets the “old” educational inequities. Teachers College Record, 123(1), 1-19. https://doi.org/10.1177/016146812112300106

Flores, N. (2016, July 23). Tim Kaine speaks Spanish. Does he want a cookie? The Educational Linguist. https://educationallinguist.wordpress.com/2016/07/23/tim-kaine-speaks-spanish-does-he-want-a-cookie/

Flores, N., & Rosa, J. (2015). Undoing appropriateness: Raciolinguistic ideologies and language diversity in education. Harvard Educational Review, 85(2), 149-171. https://doi.org/10.17763/0017-8055.85.2.149

García, O. (2009). Education, multilingualism and translanguaging in the 21st century. In T. Skutnabb-Kangas, R. Phillipson, A. K. Mohanty, & M. Panda (Eds.), Social justice through multilingual education (pp. 140-158). Multilingual Matters. https://doi.org/10.21832/9781847691910-011

García, O., & Wei, L. (2014). Translanguaging: Language, bilingualism and education. Palgrave Pivot. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137385765_4

Grosjean, F. (2012). An attempt to isolate, and then differentiate, transfer and interference. International Journal of Bilingualism, 16(1), 11-21. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367006911403210

Holdway, J., & Hitchcock, C. H. (2018). Exploring ideological becoming in professional development for teachers of multilingual learners: Perspectives on translanguaging in the classroom. Teaching and Teacher Education, 75, 60-70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2018.05.015

Ladson-Billings, G. (1995). But that’s just good teaching! The case for culturally relevant pedagogy. Theory Into Practice, 34(3), 159-165. https://doi.org/10.1080/00405849509543675

Lyiscott, J. (2014). 3 ways to speak English. TED. https://www.ted.com/talks/jamila_lyiscott_3_ways_to_speak_english?subtitle=en

Otheguy, R., García, O., & Reid, W. (2015). Clarifying translanguaging and deconstructing named languages: A perspective from linguistics. Applied Linguistics Review, 6(3), 281-307. https://doi.org/10.1515/applirev-2015-0014

Rosa, J., & Flores, N. (2017). Unsettling race and language: Toward a raciolinguistic perspective. Language in Society, 46(5), 621–647. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0047404517000562

Rymes, B. (2014). Communicative repertoire. In C. Leung & B. V. Street (Eds.), The Routledge companion to English studies (pp. 287-301). Routledge.

Swanwick, R. (2016). Languages and languaging in deaf education: A framework for pedagogy. Oxford University Press.

Vogel, S. (2020). Translanguaging about, with, and through code and computing: Emergent bi/multilingual middle schoolers forging computational literacies [Doctoral dissertation, City University of New York]. https://academicworks.cuny.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=5015&context=gc_etds

- PiLa-CS is a research-practice partnership focused on supporting bi/multilingual learners in CS Ed. For more information, see the Preface. ↵

- See Chapter 5 for some theories about equity and inequity that shape this guide. ↵

- In this chapter we use the term “bi/multilingual learners” to emphasize these students’ linguistic resources. We also opt to use this term because it is strengths based. We use it synonymously with “emergent bilinguals.” These terms stand in contrast to terms such as “English Language Learner” or “Limited English Proficient.” See the On Terminology section of this guide for an explanation on our use of identity-related terms. ↵

- Occitan is spoken in southern France, northern Spain, and parts of Italy. Patwah is spoken in Jamaica. ↵

- As one historical example, several hundred years ago, the northern part of the Indian subcontinent was said to speak a single language termed “Hindustani.” However, differences in language use shaped by religion, ethnicity, and the partition of India and Pakistan became codified as two named languages, Hindi and Urdu, written in different scripts. Social pressure has increased to use Persian-derived words in Pakistan and Sanskrit-derived words in India. Although many linguists still consider these registers of a single language, the difference holds power in social and political identities. ↵

- To learn more about translanguaging, check out the video Episode 2: Translanguaging 101 at https://www.pila-cs.org/videos ↵

- See Chapters 16 and 17 for more information on the Universal Design for Learning framework, another resource that helps teachers design instruction and assessment that more effectively supports students to demonstrate their learning. ↵

- To learn more about l33t speak, visit https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Leet ↵

- See On Terminology for more on our use of identity-related terms. ↵

- View Acevedo’s video at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tPx8cSGW4k8 ↵

- Watch Lyiscott’s talk at https://www.ted.com/talks/jamila_lyiscott_3_ways_to_speak_english ↵

- For more design strategies, check out resources from PiLa-CS at https://nyuscholars.nyu.edu/en/publications/strategies-for-supporting-bimultilingual-learners-in-cs-ed, and our video on the topic, Episode 3: Translanguaging Pedagogy in CS Ed at https://www.pila-cs.org/videos. You can also see images and resources from the unit Ms. Kors designed for John’s class at https://docs.google.com/presentation/d/1ZZgaVxlRQOy1tq9nuatdvDsoJoAaXZRPMabkQSefe0k/view#slide=id.g8929f6191e_0_286. ↵